Manonasha ..imp

Maharshi then continued:

Men find it hard to control their minds.

That is the often-heard complaint.

Do you see the reason?

Day in, day out, almost every hour and every minute, they spend their time gratifying their numerous desires; and they are and have been wholly engrossed in their attachment to external objects, i.e., the non-Self.

Hence, this outgoing tendency is deeply rooted and binds them like an iron chain.

This strong vasana, instinct or tendency, has to be overcome before they can obtain the placidity,

the equilibrium on which their realization has to be based.

So let them begin at once, i.e., as early as possible, to reverse their conduct and to gain incessant mind control.

Let them try to ride the mind and drive it to their goal, instead of allowing it to run away with them in any and every direction, driven by desires. They may start their endeavour with various helps.

The first help for mind control that is usually suggested to an aspirant is pranayama, breath-control or breath-regulation.

The mind, like a monkey, is usually fickle, restless, fretful and unsteady. As you tie-up and restrain the monkey, or a bull, with a rope, so you may still the mind by regulating and holding the breath. When the breath is so restrained, the mind gets calm and its activities in the shape of thoughts cease. When there is no thought, the jiva's energy runs back into the source whence all its energies issue, i.e., into the center, the heart.

Next, proceeding to consider the methods of securing the retention of breath (kumbhaka), we note these various methods suggested or employed:

The first and simplest course, the rajamarga, is simply to will the retention of the breath and rivet the attention on it.

The breath then stops at once. At first, this riveting of attention and willing may involve strain and fatigue. But this must be overcome by incessant practice, till the willing and attending become habitual. Then the mind is quite relaxed when it thinks of kumbhaka; and you are at once holding the breath and the mind lies narcotised and stilled like a charmed serpent.

There are perhaps some who find that the above course does not suit them. Let them try, if they choose, another method, that of Hatha Yoga, which also achieves kumbhaka though with enormous strain and struggle. Ashtanga Yoga (i.e., Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi) is common to all the methods. The chief characteristics of Hatha Yoga are its adoption of bandhanas, mudras, and shatkarmas. Details as to the practice of Hatha Yoga are found in special treatises devoted to it, such as Hathayoga-Pradipika.

In both Raja Yoga and Hatha Yoga, you find rechaka, pooraka, and kumbhaka. By rechaka you expel the used-up air from the lungs through one nostril into the external air. Then you proceed to pooraka, i.e., to fill the lungs by drawing a deep breath of pure air from outside through the other nostril, and then follows the kumbhaka, the important process of holding within the pure air in your chest for a gradually increasing period. If the period of rechaka is taken as one unit, usually the period of pooraka is an equal unit, and that of kumbhaka is four units. This is said to promote the purity of the nadis, that is, the subtle nerves. These and the brain are perhaps rendered more efficient for Samadhi, i.e., for concentration or meditation on that which has no characteristics or attributes. The purified nadis (nerves) and the brain, in turn, help breath-retention or kumbhaka. Breath-retention is styled perfect or Shuddha Kumbhaka, when breath is restrained in every way and completely.

Suddha Kumbhaka is also the name given to yet another method of pranayama. Here the abhyasi or aspirant attends only to the kumbhaka, leaving the periods of rechaka and pooraka without any special attention.

Of other methods, one only needs mention here. It is strictly speaking not a method of breath regulation but the figurative application of it.

Those who adopt the pure Jnana or Vichara Marga disdain to attend to such a trifle as mere physical breath, and declare that rechaka consists in expulsion from within themselves of that useless or poisonous "dehatmabudhi" or "I am the body" idea.

Pooraka (or the filling in, or drawing in of pure air into the system) consists, according to these, in the seeking and obtaining of light when they inquire into their the Self; and kumbhaka (i.e. the holding of pure air within and absorbing the same) consists, in their view, in the Sahaja Sthithi, i.e., the state of realising the Self as a result of the inquiry aforementioned.

Still others adopt the method of Mantra Japa, i.e., the incessant repetition of mantras (sacred sounds), to obtain manolaya [Manolaya is a temporary absorption of the mind in the object of meditation. Manonasa, destruction of mind, can alone give liberation.-Editor]. As they proceed incessantly with repetition of the sacred mantras with full faith and unflinching and unbroken attention, the breath (though unattended to) gets harmonised and in due course is stilled in the rapt attention of the mind. The individuality of the mind is sunk in the form of the mantra. All these become one and there is Realization. The stage when prana (breath) is identified with or lost in the mantra is called dhyana (meditation), and Realization rests on the basis of dhyana that has become a firm habit.

Lastly, we may notice another method of getting manolaya. That is, association with great ones, the Yogarudhas, those who are themselves perfect adepts in samadhi, Self-realization, which has become easy, natural and perpetual with them. Those moving with them closely and in sympathetic contact gradually absorb the Samadhi habit from them.

..................

You say, "What is the Self of myself? Please discover it for me by an inquiry into the Self, Atma Vichara." Well, well, you are that very Self that you seek. All that you have to do is to not lament and create a fuss over matters external to you, but to look at yourself, to realize yourself, the Self. You are, I repeat, the Self. You are that which you set out to seek. Your enquiry begins and ends with yourself, the Self. At first you begin in apparent darkness, you end in Realization, in Light.

This is Jnana Vichara. This is also termed Jnana Vimarsa, or Jnana.

...

So says Uddalaka Aruni to his son Swetaketu, in the Chandogya Upanishad, after each of his nine illustrations: (Tat Tvam Asi Svetaketu) 'You (first thought of as a separate ego) are That! (the one Sat or Brahman), O Svetaketu'. The ego is but an image of the Atman (Brahman). What remains therefore when the 'I', the separate ego, is thus dissolved? The pure Atman present in all, everywhere. That is to be realized. Vide Chandogya Upanishad, 62 Prapatatha, Kanda 8, 9, 10, etc.

..

Your next query is 'What use is Atma Vichara?'

No rational being acts without a purpose and an object. Everything he does or omits to do is to secure happiness and avoid pain or sorrow. Now, you have put this question as to the purpose of Atma Vichara. Why? The making of the enquiry by this very question gives you pleasure. The soul derives a pleasure in its very existence and in the exercise and resting of its faculties. The soul is conscious, its nature is thought, learning facts of theories; its nature is brought into play and it derives pleasure. Even the prospect of pleasure is pleasure - a sort of reflection. The reflection of the sun in the focus of a lens placed under solar rays exhibits the properties of light and heat from the sun. So this image or reflection known as jiva, this ego, is but the image of the great Brahman's Chaitanya locked up in a small focus of this human lens. It is naturally drawn by its affinity to its source and realizes supreme bliss in the act of realizing its nature, its identity with the One Reality.

By this very act, all its sorrows cease This is the fruit of Atma Vichara. This is mentioned in the true philosophical sense. Joy and pain are the attributes of the buddhi (intellect) or the ahankara (ego). When by Atma Vichara you realise you are not that sheath, where is pleasure or pain for you? Your real nature transcends all such feelings as pleasure and pain. So the benefit of your Atma Vichara is tangible, in the fact that you escape from all the ills and sorrows of life. What more can man desire?

..............

bhidyate hridaya gramthi means:

Maharshi:

Granthi is a knot.

The knot of the heart ties two things together: the Supreme Brahman or Atma, and the appearance also of the jiva connected with a body.

The location or contact between the body and Brahman is styled as the granthi or knot.

It is by reason of that relation (or knot) that one gets the idea of a body, and the idea that he has or is a body.

The body itself is inert, but Brahman is of the nature of Consciousness. The relation between these two is inferred by the intellect.

When the body is active in the waking and dreaming states, it is so by reason of its being overshadowed or covered by the image or reflection of the pure Chaitanya, i.e., Brahman. When, however, one is asleep, or for other reasons inactive and unconscious (e.g., in faint or coma), such image or reflection is absent, and from this fact the place of the Chaitanya or Brahman in the body is ascertained or located. It is located in the heart ( hrdayam), into which the soul or ego retreats in deep sleep, ceasing its conscious activity in all parts of the body. This heart is connected with a number of nadis (nerves) and the reflection of the Chaitanya on the heart spreads from the heart through these nadis or nerves into all parts of the body. The Chaitanya is subtle like electricity; and just as electricity, which in its manifest form is seen in lights, operates through solid material-like electric wires, so this Chaitanya Jyoti, or light of Brahman, moves from its subtle form through these nadis or nerves into the entire human frame. The sun, from its place in the heavens, illumines the entire solar system; so does Chaitanya Jyoti, or the light of Brahman, taking its place in the heart, illumine the entire human frame; and when such Chaitanya pervades every part of this body, then does the embodied soul, the jiva, derive all its experiences.

There are various powers manifest in the different nadis or nerves according to the function performed by each tissue or organ into which they (the nerves) enter.

All such powers, however, are the various transformations of the one Chaitanya that permeates the nadis.

But there is one nadi called the sushumna which is specifically the nadi prominently connected with the manifestation of the Chaitanya itself. It is also termed Atma-nadi or Amritanadi.

When man is operating through the other nadis alone, he derives the impression that the body is himself,

But there is one nadi called the sushumna which is specifically the nadi prominently connected with the manifestation of the Chaitanya itself. It is also termed Atma-nadi or Amritanadi.

When man is operating through the other nadis alone, he derives the impression that the body is himself,

and that the external world is different from him,

and hence he is filled with abhimanam or dehabhimanam, i.e., 'I-am-the-body idea'.

When, however, he renounces these ideas (i.e., that the body is himself and that the world is different from himself) and expels the abhimanam (I-am-the-body idea) and enters on the enquiry into the Self, Atma Vichara, with concentration, then he is said to be "churning the nerves" (nadimathanam).

By such churning, the butter of the Atma or Self is separated from the nadis in all parts of the body and the Self shines in the Amrita or Atma-nadi.

Then is the Self or Brahman realised.

Then one perceives nothing but the Atman (Brahman) everywhere.

Such a person may have sense objects presented to him and yet, even when receiving those impressions, he will receive them as himself,

not as different from himself, which is the view of the ignorant.

In everything that he sees, the ignorant one perceives form.

The wise one perceives Brahman inside and outside of everything that he sees. Such a person is said to be a Bhinna-granthi, i.e., the Knotless. For him the knot which tied up matter or body with Brahman has been severed. The term granthi or knot is applied both to the nadi-bandha, or physical knot in the nerves (something like the ganglia), and the abhimana or attachment to the body resulting therefrom. The subtle jiva operates through these knots of nadis when he perceives gross-matter.

When the jiva retreats from all these nadis and rests in the one nadi, i.e. Atma-nadi, he is termed the Bhinna-granthi, or the Knotless; and his illumination results in his achieving Self-realization.

Let us take the case of a red-hot piece of iron. Here, what was formerly the cold, black iron is now seen suffused with and in the form of fire. Similarly, the one dull, cold and dark jiva, or even his body, when overpowered by the fire of Atma Vichara (knowledge of the Self), is perceived to be in the form of the Atman.

When a man reaches that stage, all the vasanas (tendencies), derived (it may be) from many previous lives and connected with the body, disappear.

The Atma, realising that it is not the body, realises also the idea that it is not the agent performing karma or action and that, consequently, the vasanas or fruits resulting from such (antecedent) karma do not attach to it (the Atman).

As there is no other substance besides the Atman, no doubts can trouble that Atman. The Atman that has once burst its knots asunder can never again be bound. That state is termed by some Parama Sakti (highest sakti) and by others Parama Santi (supreme peace).

K: Both the ignorant man and the man of Realization in their actual daily life perceive the experiencer, experience, and the objects experienced. How is the Realised one better off than the ignorant person?

Maharshi: Because the Self-realised sees the unity of the Real amidst the multiplicity of appearances, whereas the ignorant man only sees and succumbs to the appearance of plurality.

The former sees himself, i.e., the experiencer, the objects experienced, and experience as one and the same Self, and the latter does not. To the latter, who does not see the Self, everything is different.

Where, for one, everything has become Atma alone, what is there to be seen, and by whom?

K: Can we know the Real (Swarupa) without its activity?

Maharshi: No, we do not know the unmanifest Real apart from its manifesting activity. Energy (Sakti), according to Saktas, has two names, the activity (vyapara) and support (asraya). Activity is creation, maintenance, reabsorption (pralaya), etc. The support is nothing but the Real, the Supreme (Swarupa). The Real is all, underlies all and needs the support of none. Such is the truth about the Real, its energy and activity. Multiform existence is the result of activity, and activity presupposes energy with the Supreme. When the Supreme is unclothed with energy, no activity arises, nor the Universe. In the endless whirl of creation and re-absorption, when re-absorption occurs, activity merges in the Supreme.

All human experience is impossible in the absence of energy (Sakti); no creation, no knowledge, and no triad can exist then. In the language of Saktas, Sakti (energy) is the Supreme, the one Real, and takes the name of activity (vyapara) in the act of creation, etc., and the name of Self (Swarupa) by reason of its being the support or sine-qua-non of activity.

If one considers that change (chalana) is the distinguishing characteristic of energy, then it must be admitted that we posit the existence of the Supreme Substance as that on which the play of energy or change takes place. That Supreme Substance is differently styled by different sets of persons. Some call it Sakti and others Swarupa; some call it Brahman, and others Purusha.

Reality (Satya) is to be viewed in two ways: first by its description and next by its nature or constitution, i.e., as the thing in itself. By description and name, that is, through speech, one tries to approach it and get an idea of it. But the Reality, as it is in itself, can only be realised; it cannot be expressed. The description given of it in the Vedas is:

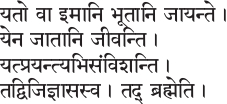

That Source, the maintenance, and end of all refers to its external attribute — activity, in order to give the learner an idea of it. But the thing as it is in itself must only be immediately (directly) realised aparokshanubhuuti).yato vaa imaani bhuutaani jaayante

yena jaataani jiivanti

yat-prayantyabhisam-vishanti

tad-vijijnaasasva tad brahmetiTo him, verily, he said: Whence indeed these beings are born; whereby, when born, they live;

wherein, when departing, they enter; That seek thou to know; That is Brahman.

The wise (i.e., Vedantins) say that the basis or sine-qua-non of energy (Sakti) is the Self (Swarupa), and that its activity is its attribute. By inquiring into the cause or root of that activity, one reaches its basis, the Self.

Substance and attribute, that is, Self and its basis are inseparable. Let any one try to separate them, his mind retires baffled from the task.

It is always by its attribute of activity that the Self is made known and (from this point of view) the attribute, activity, is therefore associated always with the Substance, the Self.

But this activity is (in reality, from the point of view of the Self-realised) not distinct from the Eternal Self.

The distinction between substance and attribute is the result of illusion.

If the illusion disappears, the Self alone remains.

sep oct 2010 ends, 100/209 talks with ramana maharshi vol 1

a-mani bhava..duality no longer cognized

nov dec 2010

Such freedom or Mukti is attained by the wise one who passes from his Sushumna-nadi in the upward path by the Archinathi Margam; by the light of wisdom emanating there, Mukti is attained.

By the Grace of the Lord, the upasaka whose mind is matured by yoga, attains this excellent Nadi-dwara Gati.

sep oct 2010 ends, 100/209 talks with ramana maharshi vol 1

a-mani bhava..duality no longer cognized

nov dec 2010

Such freedom or Mukti is attained by the wise one who passes from his Sushumna-nadi in the upward path by the Archinathi Margam; by the light of wisdom emanating there, Mukti is attained.

By the Grace of the Lord, the upasaka whose mind is matured by yoga, attains this excellent Nadi-dwara Gati.

To him comes the power of traversing all worlds at pleasure, entering into any body at pleasure, and granting all boons to anyone at pleasure.

...............

shiva ananda lahari

Just as the intellect considers the oyster shell as silver, the glass flint as a gem, the flour and water paste as milk and the mirage as water,

Some say that Kailasam (the Seat of Siva) is the place to which released souls go; others say it is Vaikuntam (the abode of Vishnu), yet others say it is Surya-Mandalam, the orb of the Sun. All these worlds to which these released souls go are as real and substantial as this world is. They are all created within the Swarupa by the wonderful power of Sakti.

It is only Realization that can ensure a rooting out, i.e., the permanent removal of these obstacles of doubt and delusion.

When the mind or jiva goes through various outside experiences, even by exploring hundreds of Sastras, without realising and staying in the Atman, one does not obtain what is styled Aparoksha Jnana, i.e., Self-Illumination directly realised.

If, however, one has obtained such Realization, then one gets Sakshatkara, or immediate knowledge of the Self, and that is Moksha — that is the highest Nishta.

As the Ankola seed is attracted to its stem, the iron to the magnet, the wife to her lord, the creeper to its tree, the river to the ocean, so the soul attracted stands ever at the feet of the Lord. This attraction is termed devotion, Bhakti.

— Sivanandalahari, verse 61

...............

shiva ananda lahari

Just as the intellect considers the oyster shell as silver, the glass flint as a gem, the flour and water paste as milk and the mirage as water,

likewise, the dull witted in delusion as to who is god, worships one other than you, Oh Pasupati,

not having considered you, the supreme self luminous lord in their minds.

For the sake of a flower, the dull witted one enters the deep lake and the lonely, terrible forest and wanders in the huge mountain. Having submitted the one lotus flower of the mind to you Oh Umanatha, man does not know to remain in a state of happiness. Why alas !

For the sake of a flower, the dull witted one enters the deep lake and the lonely, terrible forest and wanders in the huge mountain. Having submitted the one lotus flower of the mind to you Oh Umanatha, man does not know to remain in a state of happiness. Why alas !

Whether the birth is in human form or divine form, the form of an animal in the mountain or forest, a mosquito, a domestic beast, a worm or bird etc., how does that body matter if the heart here is intent always in taking pleasure in the wave of supreme bliss by remembrance of your lotus feet.

Let him live in a cave or a home, outside or in a forest or on the mountain top, in the water or in fire. Do tell, what purpose is (such) a residence ? He whose mind also (in addition to the external senses) is always fixed on your feet, Oh Sambhu, he alone is a supreme saint, he alone is a happy man.

In the worthless circuit of worldly life, not conducive to self contemplation, I, the blind one am wandering, by virtue of (my) dull wit and am worthy of protection by your supreme compassion. Who other than me is more pitiable to you, a great expert in the protection of the poor? Oh Pasupati, in all three worlds who can be my protector other than you ?

.................. Thus devotion to a personal God gets transformed or ripened gradually into devotion to the Impersonal,

which is the same as Vichara (enquiry) and Realization.

Investigation into the Self is nothing other than devotion....vivekchudamani verse 32

Devotion may at the outset be by fits and starts.

Investigation into the Self is nothing other than devotion....vivekchudamani verse 32

Devotion may at the outset be by fits and starts.

That need not depress the aspirant, for it will develop and become steadier and flow finally in an unbroken current.

When devotion (personal) is ripe, a moment's instruction (Sravana) suffices for the next step in Jnana.

Faith helps in the development of one's intuition and the attainment of complete illumination – Cosmic Consciousness. Thus, the weak aspirant's first efforts at devotion, through name and form at broken intervals, and for attaining finite or lower ends, ultimately carry him beyond all name and form, into an unbroken current of love to the Absolute. This is Salvation (Mukti).

......Ramana Gita ends....................

......Ramana Gita ends....................