https://archive.arunachala.org/docs/ganapati-muni/collected-works/sri-ramana-gita/

CHAPTER I

Kavyakantha Ganapati Sastri: For Moksha (release from the bondage of samsara) sadhana (i.e., means to be adopted for practice) has to be considered. Some seem to opine that all that is necessary is Satyā-satya viveka, the (careful) discrimination between what is ultimate truth or reality and what is not such truth or reality. Is that sufficient? Or is it necessary to adopt other means also?

Maharshi: Moksha is release from bondage; bondage is really ignorance; and ignorance can only be expelled by enlightenment.

If the expulsion is to be complete and permanent, the enlightenment also must be complete and permanent.

That is, one must always remain realizing That.

Remaining in the realization of That is termed Atmanishta. This alone removes all bondage, that is, secures Moksha.

K.G.S.: But is not viveka the means to secure Atmanishta?

Maharshi: Viveka is the discrimination of the (eternal) Real from the unreal. It helps to secure vairagya, dispassion or freedom from emotions such as joy, sorrow, etc., which disturb the placidity and equanimity of one's mind, and thus viveka proves to be a useful and a necessary preparation for attaining Atmanishta, i.e. firmness in Jnana (Enlightenment.)

The knowledge of Satya or the Real secured by viveka (discrimination) is not the same as (but only the basis of) Jnana (Enlightenment) or Atmanishta (i.e., firm self-realization).

The former is still in the stage of chitta-vritti, an intellectual process, while the latter is not under it's influence.

but is intuition, something in which the chitta (mind or intellect) has ceased its activities.

The former state still retains the duality of reality and unreality, and the contrast between the two.

In the latter, i.e., the state of the Jnani, all contrasts and duality are swallowed up and there is only ineffable Realization.

The intellectual viveki knows and reasons mediately (paroksha).

The intuitive Jnani feels the truth, the Real, directly and immediately (aparoksha).

The Jnani is not like the intellectual viveki.

He regards the Jagat (Visvam), i.e., the phenomenal universe, as unreal, or as in no way different from himself, the Self.

K.G.S.: Is sastra charcha, the study and exploration of scripture, sufficient to attain Moksha, or should one seek the aid of a Guru and practice meditation (i.e., upasana) to attain Jnana (realization)?

Maharshi: Mere scriptural learning is insufficient.

Certainly, practice of meditation and concentration is needed for realization.

But what does that term upasana (practice) imply? It means that the aspirant is still conscious of his separate individuality and fancies himself to be making efforts to attain something — some Jnana not yet known to be himself.

He ultimately arrives at the truth, the realization that all the time (including the time of practice) he has been (as he is and will be) himself the Self — beyond the concept of time.

Though it is that state of realization (Sahaja Sthithi), or natural state of the Self that has been throughout all the time of practice (as nothing else exist), he calls it "upasana" or practice of meditation.

Since his realization is not yet perfected; he, the thinker, or the subject, fancies he is going through a process of thinking or meditation upon an object, viz. Ishwara.

When perfected, his state is termed Jnana, or Sahaja Sthithi, or the Atman, or Swabhava Samsthithi, or Sthitha Prajnatvam.

It may be described further as the state when vishaya  jnanam, i.e., knowledge of the objective world, the non-self, has been entirely effaced and nothing remains but a blaze of consciousness of the Self as the Self (Swabhava Samsthithi).

jnanam, i.e., knowledge of the objective world, the non-self, has been entirely effaced and nothing remains but a blaze of consciousness of the Self as the Self (Swabhava Samsthithi).

K.G.S.: Does the aspirant after he attains firm Enlightenment (Sthitha Prajnatvam) retain a sense of his personality (self-consciousness)? Is he aware then that he has attained perfectly firm Enlightenment; and does he perceive that (1) from the entire effacement of his knowledge of the objective world or non-self, or (2) from perfection of his Enlightenment (Prajnatvam)?

Maharshi: Yes, the perfectly Enlightened, the fully attained Jnani, the Self-realized, certainly realizes himself as such.

There can be no doubt there. Doubt or uncertainty is for the mind or intellect, and has no place in that perfection of Realization or Enlightenment.

Perfection is seen

(1) by a negative sign, the cessation of all vasanas, i.e., tendencies of the mind to act in consequence of previous "attached karma" (action), and

(2) by the positive sign of his incessant consciousness (Chidatmakaratha), which is also termed "Mownam".

As for perfection of Jnana, the distinction is often drawn between Jnana and Vijnana, the latter referring to realization.

The Jnani is said to be not merely Jnana-Swarupa, i.e., of the nature of Enlightenment, but also Swatmarama or Anandamurti, which means that he is experiencing and enjoying the Self as Jnanam or Anandam.

But this is a dualistic metaphor. In point of fact, that which is (Sat), is but one. There is no separate thing as its enjoyment, or an object, or a quality for it to enjoy.

But thought has to be expressed to others "in matter-moulded forms of speech" and so we proceed into finer and finer analysis by means of similes, metaphors, etc., even as the Reality defies expression.

On account of the use of such figurative language, however, the question is raised whether the Jnani experiences or realizes his Jnanam.

What remains after all elimination is best described as Sat, that which is, Chit, consciousness or illumination, and Anandam or happiness — all three terms referring to one and the same substance.

That is really not existence, nor illumination, nor happiness, nor substance, nor personality as we conceive them now.

But these are the expressions or ideas which suggest to us that Supreme State, that goal, "Sa kashtha sa para gatih," That is Supreme, That the highest goal. (Katha Upanishad I-3-11)

K.G.S.: Well, the Jnani knows himself as such, i.e., as the fully attained. But can others know him to be such, and if so, by what indication?

Maharshi: Yes, it can be known.

The mark by which perfect realization is indicated is Sarvabhuta Samattva, which means equality or sameness toward all.

When one finds the same Atma or Self in all the various moveable and immoveable objects and his behaviour indicates the sense of equality, that constitutes the hallmark of the Jnani, Gunatita, Brahman, etc., as he is variously called.

Equality means here, in practice, the accordance of treatment appropriate to each, without undue preference or undue avoidance as described in the Bhagavad Gita:

32. He who, through the likeness of the Self, O Arjuna, sees equality everywhere, be it pleasure or pain, he is regarded as the highest yogi. (Chap. VI)

24 & 25. Who is the same in pleasure and pain, who dwells in the Self, to whom a clod of earth, stone and gold are alike, who is the same to the dear and the unfriendly, who is firm, and to whom censure and praise are as one, who is the same in honour and dishonour, the same to friend and foe, abandoning all undertakings — he is said to have transcended the qualities. (Chap. XIV)

K.G.S.: Does the practice of yoga culminating in samadhi (absorbed concentration or ecstasy) serve only the purpose of Self-realization or can it be utilized to secure also other and lower objects, such as the attainment of temporal ends?

Maharshi: Why, samadhi (i.e., the Yogi's perfect concentration) serves both purposes — Self-realization and the securing of lower objects.

K.G.S.: If one starts his practice of yoga and develops samadhi (absorbed concentration) to secure lesser objects, and before attaining these attains the greater object of Self-realization, what happens about the lesser objects? Does he attain these also or does he not?

Maharshi: He does. The karma (or effort) to reach lesser objects does not cease to produce its result and he may succeed in achieving these even after securing Self-realization. Of course, on account of such realization, there will be no exultation or joy at the lesser successes. For that which feels emotion, the mind, has ceased to exist in him as such, and has been transmuted into Prajna, Cosmic Consciousness.

— continued in the Sep-Oct issueChapter II

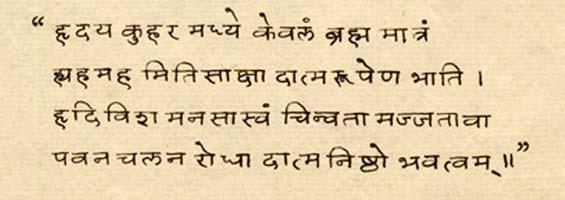

The Swami's Verse

On a certain day during the winter of 1915, Sri Ramana was sitting in Skandasramam. Before him sat Jagadeesa Sastri, a young man well-versed in Sanskrit who had previously (and has since) composed Sanskrit verses. On that day Jagadeesa Sastri wrote on a piece of paper, as part of the first line of a stanza, the words 'Hridaya Kuharamadhye,' and his mind, in spite of effort (or perhaps on account of it), could not proceed further and he did not complete it. Then Maharshi asked, "What is it you are writing?" Sastri handed over his paper.

Maharshi said, "Go on. Complete the verse."

Sastri replied, "I am trying, but my mind refuses to work."

Maharshi then took up the verse, and then and there completed the verse as given below. The verse was taken later to Kavyakantha Ganapati Sastri at Mandassa, who later incorporated it into his Ramana Gita as Chapter II. In fact, this, strictly speaking, is the Ramana Gita, as it was sung (or was a song composed) by Sri Ramana.

The Stanza runs thus:

hyahamaham-iti sakshad, atma-rupena bhati

hridi visa manasa swam, chinvata majjata va

It means:

Kavyakantha Ganapati Sastri on a later occasion requested the Maharshi to explain fully the meaning of the term "Heart" and the facts stated about it, for the purpose of Self-realization. Maharshi's reply is embodied in Chapter V.

Chapter III

The Chief Aim of Life

7-7-1917

The year 1917 was full of philosophical interest to the disciples at the Ashram. Kavyakantha had now come back to Tiruvannamalai after his trips and was anxious to use this opportunity to place before the Maharshi doubts and difficulties often experienced by the disciples in their effort to understand the scriptures and to elicit the exact drift of his teachings. He invited leading disciples to come forward and place all their difficulties before the Maharshi, so that he might gather all the replies into one volume of Sanskrit verse and name it 'Sri Ramana Gita'. As each set of these questions was put and replies elicited, Kavyakantha took them down first in 'sutra' form (i.e., as aphorisms), and almost immediately rendered them into Sanskrit verse. The Sri Ramana Gita was thus ready before the end of 1917 and it was translated into Telugu and Tamiḷ by Vellore S.Narasimhayya, now known (i.e., since his adoption of sannyasa in 1927) as Pranavananda. These translations were printed and published only in 1923.

On the 7th of July of that year, the questions were begun by one Ganjanana [1], a young man full of fervid devotion. He hailed from North Kanara District of the Bombay Presidency and was well versed in Sanskrit. Srimad Bhagavatam and Maharatta and Canarese songs relating to Sri Krishna and Sri Rama were the delight of his heart. He was here at Arunachala for a few months and attached himself to Kavyakantha and the Maharshi, and composed a "Vibhaktijashtaka" of eight stanzas in praise of the latter. He lived on begged food, leading an austere life of a bhikshu. When Maharshi and the disciples started on their Giripradakshinam (circumambulating the Arunachala Hill on foot), Gajanana would be a very prominent figure, as he would sing devotional songs and dance frequently in ecstasy. He used his opportunities of being near the Maharshi to remove his own doubts as to the Jnana Vichara Marga, i.e. the path of Self-enquiry, leading to Self-realization.

His first question to Sri Ramana Maharshi (reminiscent of the central question in Srimad Bhagavatam by King Parikshit to Sri Suka Maharshi) was: "In this samsara, or whirl of births and deaths undergone by the jiva (the soul), what is the chief thing a man has to do?"

Maharshi: Well, your question is what you as a man should do in regard to your karma, action; and it asks about the most important duty. You wish to arrange duties in the order of their importance, and this importance is based on the value, to you, of the fruits of each karma. So, in short, you are inquiring into your appropriate karma and the value of its fruits. Now, does not the karma and its importance depend plainly on the individual who is to perform the karma and reap the fruit? If so, then, as a preliminary to this investigation, first inquire who is the person who does the karma and tastes the fruit. In other words, start the inquiry "Who am I?" for yourself: i.e., the inquiry into yourself which, almost immediately becomes the inquiry into the Self, with a view to attain Self-knowledge or Self-realization.

This is therefore man's chief duty.

Gajanana: Again, Revered Sir, what briefly are the means to attain this Self-realization; and as for the means already suggested, namely the inward inquiry, or the grand pratyagdrishti, how are we to attain that?

Maharshi: Well, briefly put, the means to attain Self-realization are these:

First, the mind should be withdrawn from its objects; the objective vision of the world must cease.

Secondly, the mind's internal operations also must be put an end to.

Thirdly, the mind must thereby be rendered characterless (nirupadhika) and must continue characterless firmly; and

lastly, it must rest in pure vichara, contemplation or realization of its nature, i.e. itself. This is the means for pratyagdrishti or darsana, also termed antarmukham, the inward vision or inquiry.

Gajanana: How long has one to go on with his niyama, disciplinary regulation (such as regulation in quantity and quality of food, sleep, exertion, etc.)? Is he to adhere to them till he attains Yoga Siddhi (i.e. till he achieves success in his yoga)? And do they prove useful right up to the end of the course?

Maharshi: Yes, the spiritual aspirant in his onward career of yoga is helped by such disciplinary regulations. Once he attains success and reaches his goal, the regulations drop off by themselves.

Gajanana (adverting to the answer to his first question, asked again): Revered Sir, as for the goal that is attained by firm, characterless vichara mentioned just now, cannot the same goal be attained by mantra japa, repetition of mantras (sacred syllables)?

Maharshi: Yes. If the mantra japa is unbroken and performed with an undeflected current of attention and with due faith, equal success is achieved. Even the mere Pranava [2] Japa would suffice. You see that by such a japa (of either the Pranava or other mantras) the mind is deflected from its operations regarding the objective world; and then, by identifying oneself with the mantra, one attains the (nature of) Atman.

Chapter IV

What is the Nature of Jnana — Realisation

On the 21st July, 1917, Kavyakantha queried the Maharshi again.

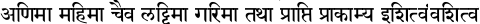

Kavyakantha: What is the "State of Jnana"? Is it the mental process ![]() [1] (I am Brahman), or the idea

[1] (I am Brahman), or the idea ![]() (Brahman is myself), or the idea

(Brahman is myself), or the idea ![]() (I am everything), or the idea

(I am everything), or the idea ![]() (Everything is Brahman); or is Jnana different from all these four ideas?

(Everything is Brahman); or is Jnana different from all these four ideas?

Maharshi: All these mental states, processes or ideas are certainly only the operations of the mind. But that which is termed Jnana is not a mental state or process. It is ![]() , i.e., Being, remaining or existence in the Self as such.

, i.e., Being, remaining or existence in the Self as such.

Kavyakantha: Then, Sir, is not the Self – Atman or Brahman (God) – reached by the mind? In fact, while the Mundaka Upanishad, III, i. says [sanskrit, to be transliterated shortly] (This subtle Self has to be known by the mind), [transliteration needed] (It is to be seen by the sharp eye of the seers of the subtle), and the Katha Upanishad IV.ii. says of Brahmana: [transliteration coming] (By the mind alone is this to be attained), while Taittiriya Upanishad, II.9. says [tranlsiteration coming] (Whence words retire baffled, as also the mind); and Brahman is repeatedly styled as [translit coming] (Not to be reached by speech or mind). How is this conflict to be reconciled and which is the truth?

Maharshi: All sets of texts are true. It is the mind that sets out on the enquiry into the nature of the Self. But in the course of its efforts to reach Brahman, it gets transformed and is seen to be Brahman. It ceases to have any separate existence.

(Requested later to elucidate this matter further, Maharshi said):

"In a sense, it is by the mind you reach Brahman.

But perhaps it will be better to stick to the more accurate expression that it is Brahman alone that realises itself,

and that the mind as such does not. What realises is not the mind as such, but the mind transformed into Purna Prajna or "Cosmic Consciousness".

By way of analogy, we may take the case of a mighty river that flows into the ocean. The waters which formerly took the name of the "river", later take the name of "Ocean". One would not refer to the river as samudrakara nadi, i.e., the "river in the form of the ocean." The mind is the separate, broken (khanda) entity which starts the enquiry; but as it progresses, it develops, alters its nature and form, and finally loses these and itself in the limitless, infinite, and undifferentiated (akhanda) ocean of Brahman. The mind may thereafter be referred to as brahmakara manas, i.e., the mind in the guise of the Absolute.

But perhaps it will be conducive to clarity if we briefly say, in popular language, that there has been manonasa, or the disappearance of the limited, finite mind and that Brahman is realized not by chitta vriti, i.e., mental operation, but by Purnattva or Swabhava Samsthiti, the perfection of Self -realization.

Maharshi had elucidated this matter by another illustration in the third stanza of his "Arunachala Ashtaka"(2)

Which means, as addressed to God Arunachala who is considered to be identical with Brahma:

Thinking of Thee without thinking (i.e., play of intellect), one's form melts away as that of a sugar doll entering the sea.

Chapter V

What is the Hridaya (Heart or Centre)?

On the 9th of August 1917, Sri Ramana Maharshi sat up at night in the Skandasramam. Kavyakantha and other bhaktas had gathered at his feet. For the benefit of all, Kavyakantha requested the Maharshi to explain fully 'the Heart' (![]() ) mentioned in his poem composed in 1915. [See Sep/Oct 2009 Newsletter].

) mentioned in his poem composed in 1915. [See Sep/Oct 2009 Newsletter].

Maharshi thus answered: ![]() , i.e. the Heart (or Centre), is that from which all thoughts spring. A description of it is given in various passages of the Vedas:

, i.e. the Heart (or Centre), is that from which all thoughts spring. A description of it is given in various passages of the Vedas:

The above comparison of the Heart to the plantain bud or lotus bud and various other physical descriptions are given to assist the yogi's practice of meditation.

How do we proceed to trace all thoughts to their source, you may ask. Well, let us discover if all thoughts could in the first place be traced to some one thought as their base of operations, and let us then go deeper and find the source of the basic thought. Is there then any such basic or fundamental thought underlying all other thoughts? Do you not see that the thought or idea 'I' – the idea of personality – is such a root thought?

For us, Maharshi explained later, whenever any thought arises, these questions arise and should be raised by the aspirant aiming at Realisation: 'Does this thought exist independently of any person thinking, or does it exist only as the thought of a person, and if the latter is the case, to whom does it arise?' The answer is: 'This thought arises only as a person's thought and this thought arises in me.' So the 'I' idea may be regarded as a stem from which other thoughts branch forth.

Next let us see the root source of this (stem). But how? Dive deep in ecstatic concentration within yourself (i.e. within the 'I' thought) and perceive its source. There is nothing there to perceive in or through the senses. You have no guidance from sensation and rationalization for this search.

But if you have the right intuition, the Centre '![]() ' is immediately felt

' is immediately felt

and the above or former 'I' which inquired disappears into this 'the Centre.'

Thus, '![]() ' or the heart centre is the source of the 'I. thought and of everything else.

' or the heart centre is the source of the 'I. thought and of everything else.

The term '![]() ' (Heart) is however persistently identified by some who practice yoga with one of their six centres

' (Heart) is however persistently identified by some who practice yoga with one of their six centres ![]() (chakram), i.e., their fourth centre called the

(chakram), i.e., their fourth centre called the ![]() (anahata chakram) situated in the chest.

(anahata chakram) situated in the chest.

These yogis admit that '![]() ' denotes the source or abiding place of the personality.

' denotes the source or abiding place of the personality.

Well then, if these yogis wish to trace or promote the development of their personality or soul from its source or abiding place to its highest reach, as they profess to do, they should start its course from ![]() (anahata chakram),

(anahata chakram),

reworded: start from anahata, rather than muladhara

whereas they invariably start their course from ![]() (muladharam) which they style their first chakra.

(muladharam) which they style their first chakra.

Hence one is perhaps well advised to confine the term, i.e., 'the Centre', to the Universal Centre or Brahman.

Brahman is often indicated in scripture as ![]() (ayam hrit), two words which make up '

(ayam hrit), two words which make up '![]() ' (hridayam) when conjoined. Even the practicing yogi does not identify the '

' (hridayam) when conjoined. Even the practicing yogi does not identify the '![]() ' (Heart) or

' (Heart) or ![]() (anahata) with the organ forming the centre of blood circulation (with its auricles and ventricles), and in the above stanza (vide Ch. II) the Heart '

(anahata) with the organ forming the centre of blood circulation (with its auricles and ventricles), and in the above stanza (vide Ch. II) the Heart '![]() ' is not used in a physiological sense, but rather as a metaphor and refers to the centre of consciousness.

' is not used in a physiological sense, but rather as a metaphor and refers to the centre of consciousness.

There is no harm, however, in taking '![]() ' to indicate an actual spatial region as is done in various parts of the scripture.

' to indicate an actual spatial region as is done in various parts of the scripture.

There, '![]() ' is said to be on the right side of the chest (not on the left where the blood propeller is situated).

' is said to be on the right side of the chest (not on the left where the blood propeller is situated).

From it radiates the sushumna nadi (or nerve), up which the current of consciousness or light goes to sahasrara (the thousand petalled – evidently referring to the brain with its numberless cells).

From that sahasrara the light of consciousness passes again (evidently through the nerves) to all parts of the body and thereby the outside world is experienced by one.

But if the experiencer views the experienced object as something distinct from himself, i.e., from the Self, then he is caught up in the whirl of samsara, the wheel of metempsychosis, or chain of births and deaths.

The sahasrara (i.e., brain) of the Atma Nishta, i.e. the Self-realizer, is pure light or enlightenment.

If any flitting or passing desires approach it, they perish therein immediately.

They have no soil to flourish upon there.

The sankalpas or seeds of desire that occur in the Atma Nishta, staying in pure light or suddha sattva, are referred to in the Upanishads as getting parched or fried.

Such a ![]() (brishtabijam) does not give birth to fresh vasanas (tendencies) or karma (action),

(brishtabijam) does not give birth to fresh vasanas (tendencies) or karma (action),

as they consume themselves, "nor leave a wrack behind."

This expression is frequently found in other Upanishads, in Vasishta and the works of Sri Sankaracharya, but this reference will suffice.

With the pure light mentioned, outside objects ![]() (vishayaha) are sensed or experienced, and their impressions received.

(vishayaha) are sensed or experienced, and their impressions received.

But, if these impressions are colored or swallowed up in the prevailing non-differentiation of the perfected yogi (Self-realized one), his yoga or Self-realization is not marred thereby.

Even when receiving outside impressions, the yogi maintains his consciousness of the unity of existence; and it is this state of central conscious-unity with a (so to speak) peripheral experience of objects (the central light swallowing up the peripheral rays), that is called Sahaja Sthiti.

But when the yogi completely shuts out cognizance of outside objects, his state is described as Nirvikalpa Samadhi, i.e., pure concentration, or the Absolute Consciousness without attributes or characteristics.

What are these objects which constitute the external universe? The entire universe or macrocosm is found in man, the microcosm. The entire man is found in the Heart, or Ultimate Centre. Ergo, the entire universe is found within that Centre, the Heart '![]() .' Again, looked at in another way, the external world does not exist without the mind perceiving it.

.' Again, looked at in another way, the external world does not exist without the mind perceiving it.

That is, unless a mind perceives and notes the existence of the worlds, how is that existence to be posited?

And the mind does not exist without the Centre '![]() .' Ergo, the entire world of experience ends at the Centre. The respective positions of the Heart (the Centre) and the mind may be illustrated by an analogy. What the sun is to the solar system – the origin of all, the supporter of all, and that which lights up all – that, the Centre (i.e., the Heart, or that which has intuition), is to man. What the moon is in the external universe, casting a delectable but uncertain light, incapable of creating or sustaining real life or throwing clear light on all objects, that the mind is when it works in or with the brain (sahasrara). Just as the moon borrows its light from the sun, so does the mind derive its power of knowing from the Centre, or Heart. It is when man has no intuition or illumination from that Centre or Heart, that he sees the mind as the only basis of his conscious activity, just as one may have, at night (i.e., when there is no sun), to be content to work by moonlight.

.' Ergo, the entire world of experience ends at the Centre. The respective positions of the Heart (the Centre) and the mind may be illustrated by an analogy. What the sun is to the solar system – the origin of all, the supporter of all, and that which lights up all – that, the Centre (i.e., the Heart, or that which has intuition), is to man. What the moon is in the external universe, casting a delectable but uncertain light, incapable of creating or sustaining real life or throwing clear light on all objects, that the mind is when it works in or with the brain (sahasrara). Just as the moon borrows its light from the sun, so does the mind derive its power of knowing from the Centre, or Heart. It is when man has no intuition or illumination from that Centre or Heart, that he sees the mind as the only basis of his conscious activity, just as one may have, at night (i.e., when there is no sun), to be content to work by moonlight.

At such a time the man is ignorant (pamara), as he does not see the source of all light (i.e., consciousness), viz. the Real, the Atman, but sees objects with the help of the mind alone, and sees them as different from himself; hence, he wanders as in a maze.

The Jnani, on the other hand, stationed in the Centre, sees within it the mind, no doubt; but that mind is of as little significance to him as the moon when seen in daylight.

The term Prajna has for its superficial denotation (Vachyartha) the mind, but it is in reality, i.e. in its essential content (lakshyartha), the Centre (![]() ), the Heart. Brahman is naught but that.

), the Heart. Brahman is naught but that.

To those who perceive with the help of the mind only, the difference of seer and seen exists, but to those at the Centre, they are one and the same.

Now, as for the advice given in the second half of the stanza (i.e., Chapter II) that one should enter into the Self in the Heart, there are, apart from spiritual enlightenment, other instances of the mind disappearing into the Centre by reason of deep sleep, excessive emotions of joy, sorrow, terror, rage, catalepsy, possession or coma.

These also strike the mind and drive it into its source.

However, in these states, there is no illumination or even awareness of one's individuality, whereas in the condition of Samadhi, the Self-realization achieved by the yogi, one has such awareness and illumination. That is the difference between Samadhi and the above mentioned states.

CHAPTER VI

What is Manonasa (Mind-Destruction)?

21-8-1927

Kavya Kantha: Bhagavan has said that the re-entry of the mind into the heart as effected by the Jnani and known as the manonasa of Samadhi, is radically different from the disappearance of mind in disease, etc. The disciples desire to know something more of manonasa and manolaya, and how they are to be effected.

Maharshi then continued:

Men find it hard to control their minds. That is the often-heard complaint.

Do you see the reason?

Day in, day out, almost every hour and every minute, they spend their time gratifying their numerous desires; and they are and have been wholly engrossed in their attachment to external objects, i.e., the non-Self.

Hence, this outgoing tendency is deeply rooted and binds them like an iron chain.

This strong vasana, instinct or tendency, has to be overcome before they can obtain the placidity, the equilibrium on which their realization has to be based.

So let them begin at once, i.e., as early as possible, to reverse their conduct and to gain incessant mind control.

Let them try to ride the mind and drive it to their goal, instead of allowing it to run away with them in any and every direction, driven by desires. They may start their endeavour with various helps.

The first help for mind control that is usually suggested to an aspirant is pranayama, breath-control or breath-regulation. The mind, like a monkey, is usually fickle, restless, fretful and unsteady. As you tie-up and restrain the monkey, or a bull, with a rope, so you may still the mind by regulating and holding the breath. When the breath is so restrained, the mind gets calm and its activities in the shape of thoughts cease. When there is no thought, the jiva's energy runs back into the source whence all its energies issue, i.e., into the center, the heart.

Next, proceeding to consider the methods of securing the retention of breath (kumbhaka), we note these various methods suggested or employed: The first and simplest course, the rajamarga, is simply to will the retention of the breath and rivet the attention on it. The breath then stops at once. At first, this riveting of attention and willing may involve strain and fatigue. But this must be overcome by incessant practice, till the willing and attending become habitual. Then the mind is quite relaxed when it thinks of kumbhaka; and you are at once holding the breath and the mind lies narcotised and stilled like a charmed serpent.

There are perhaps some who find that the above course does not suit them. Let them try, if they choose, another method, that of Hatha Yoga, which also achieves kumbhaka though with enormous strain and struggle.

Ashtanga Yoga (i.e., Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi) is common to all the methods. The chief characteristics of Hatha Yoga are its adoption of bandhas, mudras, and shatkarmas. Details as to the practice of Hatha Yoga are found in special treatises devoted to it, such as Hathayoga-Pradipika.

In both Raja Yoga and Hatha Yoga, you find rechaka, pooraka, and kumbhaka. By rechaka you expel the used-up air from the lungs through one nostril into the external air. Then you proceed to pooraka, i.e., to fill the lungs by drawing a deep breath of pure air from outside through the other nostril, and then follows the kumbhaka, the important process of holding within the pure air (in your chest) for a gradually increasing period. If the period of rechaka is taken as one unit, usually the period of pooraka is an equal unit, and that of kumbhaka is four units. This is said to promote the purity of the nadis, that is, the subtle nerves. These and the brain are perhaps rendered more efficient for Samadhi, i.e., for concentration or meditation on that which has no characteristics or attributes. The purified nadis (nerves) and the brain, in turn, help breath-retention or kumbhaka. Breath-retention is styled perfect or Suddha Kumbhaka, when breath is restrained in every way and completely.

Suddha Kumbhaka is also the name given to yet another method of pranayama. Here the abhyasi or aspirant attends only to the kumbhaka, leaving the periods of rechaka and pooraka without any special attention.

Of other methods, one only needs mention here. It is strictly speaking not a method of breath regulation but the figurative application of it.

Those who adopt the pure Jnana or Vichara Marga disdain to attend to such a trifle as mere physical breath, and declare that rechaka consists in expulsion from within themselves of that useless or poisonous "dehatmabudhi" or "I am the body" idea.

Pooraka (or the filling in, or drawing in of pure air into the system) consists, according to these, in the seeking and obtaining of light when they inquire into their the Self;

and kumbhaka (i.e. the holding of pure air within and absorbing the same) consists, in their view, in the Sahaja Sthithi, i.e., the state of realising the Self as a result of the inquiry aforementioned.

Still others adopt the method of Mantra Japa, i.e., the incessant repetition of mantras (sacred sounds), to obtain manolaya [Manolaya is a temporary absorption of the mind in the object of meditation. Manonasa, destruction of mind, can alone give liberation.-Editor]. As they proceed incessantly with repetition of the sacred mantras with full faith and unflinching and unbroken attention, the breath (though unattended to) gets harmonised and in due course is stilled in the rapt attention of the mind. The individuality of the mind is sunk in the form of the mantra. All these become one and there is Realization. The stage when prana (breath) is identified with or lost in the mantra is called dhyana (meditation), and Realization rests on the basis of dhyana that has become a firm habit.

Lastly, we may notice another method of getting manolaya. That is, association with great ones, the Yogarudhas, those who are themselves perfect adepts in samadhi, Self-realization, which has become easy, natural and perpetual with them.

Those moving with them closely and in sympathetic contact gradually absorb the Samadhi habit from them.

Self-Enquiry, Competence and Constituents

CHAPTER VII

Among the disciples of Sri Ramana Maharshi was the local fund-overseer K.Vidyananda Iyer (son of Krishna Iyer, belonging to Bharadwaja Gotra), who had served in Tiruvannamalai in 1914. He came back in 1917 for a short rest. At that time he wished to elicit Maharshi's views on certain matters of practical interest for the guidance of himself and other disciples, mainly relating to orthodox members of the Hindu community, and partly on matters of ultimate and wider interest.

K. V.: Revered Sir, may I know (1) what Atma Vichara is, (2) what benefit one derives from it, and (3) whether the same benefit may not be obtained otherwise, i.e., without such vichara?

Maharshi: What are you doing now? You are asking questions. That is, you are entering on a vichara, or enquiry. So vichara is clear enough to you. But your question is, and you wish to know, about Atma Vichara, i.e., the enquiry about Atma, the Self.

The term 'enquiry' being clear to you from your own questioning, you wish to know then what Atma, or the Self, is. You are yourself enquiring about the Self, about the Self in you, or putting the same idea in the first person, you are asking "What is my self? What is the enquiry about my self?" This is that enquiry, the enquiry now being made. This is just what happens. The Maharshi explained more fully to others, commenting on his stanza in 'Ulladu Narpadu' (Reality in Forty Verses).

37. The contention, "Dualism during practice, non-dualism on Attainment," is also not true. While one is anxiously searching, as well as when one has found oneself, who else is one but the tenth man himself?

You are really, yourself, the Self all the while, yet you do not realize it.

Just like a group of ten men who set out on a journey and crossed a river and then counted their number after crossing. Each man counted the group, omitting to count himself. They all found to their horror that they numbered only nine. Yet they could not make out if any one had been washed away by the river. They took the help of a kind and intelligent passerby who learnt of their mental distress at their fancied loss of the tenth man of their group. The wise friend counted them afresh, giving each a stroke as they filed before him. As he struck the tenth man, the group was happily surprised to discover their tenth man was not missing. Where was the tenth man all the while that they bemoaned his loss? He was there, the very person that loudly lamented the loss of himself. It is just so with you. You say, "What is the Self of myself? Please discover it for me by an inquiry into the Self, Atma Vichara." Well, well, you are that very Self that you seek. All that you have to do is to not lament and create a fuss over matters external to you, but to look at yourself, to realize yourself, the Self.

You are, I repeat, the Self.

You are that which you set out to seek.

Your enquiry begins and ends with yourself, the Self. At first you begin in apparent darkness, you end in Realization, in Light.

This is Jnana Vichara. This is also termed Jnana Vimarsa, or Jnana.

You see, Jnana Vichara is feeling your way up to your fount and source, the realization at each step of what you are. People often misuse that phrase. If someone is found to be reading the Vedas, Sastras or Kaivalya Navaneetam, or some other similar book, they say they are doing Atma Vichara.

It is no such thing. Mere study of Sastras, mere booklore is not Atma Vichara.

One can and often does go through numerous books, a whole library perhaps, and yet comes out without the faintest realization of what he is.

His memory may be crammed with apt quotations from scriptures describing Brahman, or he may even know about the insufficiency of scripture study for realization, e.g.:

This Atman is not to be attained by (mere) recitation of the Vedas, or by keenness of intellect, or by extensive hearing of Scripture. Only to him whom it chooses will Atman disclose its own Self.

This mere learning (pandityam) is not the same as realization and often proves of no service to its possessor.

Why, in some cases, it even renders a disservice? Egotism develops with study, and whether pride (darpa) and egotism (ahankara) are developed by real learning (pandityam) or by superficial study makes little difference, for they both prove serious obstacles to progress.

The Maharshi later contrasted the difference between the pandit and the illiterate in his "Ulladu Narpadu Anubandham" to the advantage of the latter, thus:

34. For men of little understanding, wife, children and such others, comprise the family. Know that for the learned, in their mind itself, there is the family of countless books as an obstacle to yoga.

35. What avails (all) the learning of those 1 who do not seek to wipe out the letters (from the book of life), 2 by enquiring 'Whence is the birth of us who know the letters?' They have (verily) acquired the status of a gramophone. What else are they, tell (me), O Arunachala!

36. It is verily those not learned that are saved rather than those for whom, in spite of all their learning, the ego has not subsided yet.

(For) the unlearned are saved from the unrelenting grip of the devil of self-infatuation; they are saved from the malady of a myriad whirling thoughts and words; they are saved from (the travail of) running after wealth. Know that it is not from one indeed (but from many an ill) that they are saved.

This ahankara (egoism), or sense of a separate self in one's Self, has to be wrecked and sunk to the bottom of the bottomless ocean. How? Seek its root, and then you root it out; enquire into the origin of this separate-seeming entity and it proves unreal. It has no reality, except as part and parcel of the Unity of the Real.

As a result of your enquiry, the seeming or only apparent 'I' (Atmabhasa) is dissolved (leena) like the salt-doll. A salt doll made of salt was originally the salt of the ocean. If immersed in the waters of the ocean it disappears, and what remains is the water alone.

Numerous other illustrations are given of this truth in the Scriptures. For example, the individuality of the river water exists only so long as it flows on the riverbed, but when you trace its origin or its destination, the identity disappears and you have only water or the ocean as the remaining truth. Similarly, drops of honey retain their separate individuality only when they are on the tree or flower from which they are gathered. The individuality of the honey is not discernible in time or space in the bee's hive or in the vendor's hands.

Similarly, taking the human ahankara (ego) with the body-idea, the same ego has passed through numerous bodies of various insects, reptiles, quadrupeds and other human forms before attaching itself to the present particular human body. Ultimately, all these forms get transformed into the matter of the Universe.

So says Uddalaka Aruni to his son Swetaketu, in the Chandogya Upanishad, after each of his nine illustrations: ![]() (Tat Tvam Asi Svetaketu) 'You (first thought of as a separate ego) are That! (the one Sat or Brahman), O Svetaketu'. The ego is but an image of the Atman (Brahman). What remains therefore when the 'I', the separate ego, is thus dissolved? The pure Atman present in all, everywhere.

(Tat Tvam Asi Svetaketu) 'You (first thought of as a separate ego) are That! (the one Sat or Brahman), O Svetaketu'. The ego is but an image of the Atman (Brahman). What remains therefore when the 'I', the separate ego, is thus dissolved? The pure Atman present in all, everywhere.

That is to be realized.

Vide Chandogya Upanishad, 62 Prapatatha, Kanda 8, 9, 10, etc.

Your next query is 'What use is Atma Vichara?' No rational being acts without a purpose and an object. Everything he does or omits to do is to secure happiness and avoid pain or sorrow. Now, you have put this question as to the purpose of Atma Vichara. Why? The making of the enquiry by this very question gives you pleasure. The soul derives a pleasure in its very existence and in the exercise and resting of its faculties. The soul is conscious, its nature is thought, learning facts of theories; its nature is brought into play and it derives pleasure. Even the prospect of pleasure is pleasure - a sort of reflection. The reflection of the sun in the focus of a lens placed under solar rays exhibits the properties of light and heat from the sun. So this image or reflection known as jiva, this ego, is but the image of the great Brahman's Chaitanya locked up in a small focus of this human lens. It is naturally drawn by its affinity to its source and realizes supreme bliss in the act of realizing its nature, its identity with the One Reality.

By this very act, all its sorrows cease ( ![]() ). This is the fruit of Atma Vichara. This is mentioned in the true philosophical sense.

). This is the fruit of Atma Vichara. This is mentioned in the true philosophical sense.

Joy and pain ( ![]() ) are the attributes of the buddhi (intellect) or the ahankara (ego).

) are the attributes of the buddhi (intellect) or the ahankara (ego).

When by Atma Vichara you realise you are not that sheath, where is pleasure or pain for you? Your real nature transcends all such feelings as pleasure and pain. So the benefit of your Atma Vichara is tangible, in the fact that you escape from all the ills and sorrows of life. What more can man desire?

Chapter VII

Self-Enquiry, Competence and Constituents

Referring to this discourse, the Maharshi was requested years later by some disciples to make the matter clear as to what is meant by ![]() (removal of all sorrow):

(removal of all sorrow):

Disciple: Does the Maharshi mean that, as a result of Realisation, there is a feeling of positive pleasure, similar to our pleasures now experienced, or is it a mere colourless negation of pain and pleasure that you refer to by that phrase? All pleasure is known to us only by our knowledge of the contrasted state of pain; and hence, no pleasure is experienced if the pain-idea is not also experienced or remembered to make the pleasure-idea clear to the experiencer at the time of the experience.

Maharshi: You are right in drawing a distinction between the pleasure experienced in the waking state and that referred to in the expression 'Bliss of the Self', Sat-Chit-Anandam. You find reference to this distinction frequently in books on this subject, as well as in your own experience.

Disciple: Pray, in what books do we find this distinction discussed?

Maharshi: See the Panchadasi and the Tamiḷ Kaivalyam, Chap. II, v. 116. Also see Vedanta Chudamani, reference to Ashta Vidanantam (eight pleasures) as being 'poli' (false) — reflections or mere appearances or illusory bliss, and Sat-Chit-Anandam or Swarupananda as the Real bliss. It is however preferable to avoid the use of the term 'positive' by referring to the former, and to use the term 'relative' for the former, and 'Absolute' for the latter. In the latter, Bliss is itself Sat, itself Chit, itself Anandam – the Three, being different names or aspects of the one Reality, the Absolute. The bliss enjoyed in deep sleep is referred to as one of the eight poli anandam, illusory pleasures, in the book Vedanta Chudamani.

K.V.'s Question: Does Maharshi also apply this ![]() (i.e., destruction of all sorrow) as a result of Atma Vichara, in the field of suggestive therapeutics, e.g., in cases of illness (as in William James' Varieties of Religious Experience, page 104) and in the practical affairs of daily life to overcome the various painful experiences met with?

(i.e., destruction of all sorrow) as a result of Atma Vichara, in the field of suggestive therapeutics, e.g., in cases of illness (as in William James' Varieties of Religious Experience, page 104) and in the practical affairs of daily life to overcome the various painful experiences met with?

Maharshi: Yes. The truth of the Self is one. Its applications are many. Sugar is one. The clever cook or lady of the house embodies it and presents it in the shape of payasam, halva, athirasam, jilebi, etc. But these are all transformations of sugar and cannot exist without sugar. The Central Substance or Truth is applied according to the peculiar needs or aspirations of each individual and to the purpose at hand. People who come here make use of the Truth for their own affairs. One, for instance, like the lady earlier mentioned, was complaining of dyspepsia and insomnia and, by applying the above Truth to herself and impressing on her mind that she was not the sickly body but the pure Atman that cannot be touched by disease, got over both her ailments. Many others have got over their stomach or other troubles here in the same manner.

K.V.: Was not Vasudeva Sastriar, when deeply afflicted with the loss of his dear child, relieved of his sorrow in this presence in the same manner? Are these all implied in ![]() character of Atma Vichara?

character of Atma Vichara?

Maharshi: Yes, such instances here are not infrequent. Maharshi then proceeded to answer K.V.'s next question:

You inquired if the above benefit of 'sarva-kleshanasa' (the destruction of sorrow, root and branch) can be derived by other means?

What other means are there that secure this result? Are you thinking of siddhis, the eight siddhis [1]

[1]

which means, the power to assume any shape at will, or dimension, any size or weight, to attain any object of desire, overlordship, influence, etc. What good will these do? Suppose you exercise all these wonderful powers, are you not still desiring and trying to fulfill that desire? And when a fresh desire breaks out and you expend your energy and attention on that, is not the net result more worry to the tossed mind? Happiness is your real goal and aim. You must ultimately come back from your diversion with siddhis and try to find yourself by inquiring, 'Who is it that wants happiness?'. You discover that happiness or bliss [which is our true nature] wants happiness or bliss, or rather that the so-called want and desire on the part of an individual is a myth, and that all along there is only the One Real in enjoyment (so-to-speak) of its Self, which is best described (however inaccurately or inadequately) as Existence-Consciousness-Bliss, Sat-Chit-Anandam.

K.V. next questioned Maharshi:

Who is the Adhikari, i.e., the person competent to launch on this Atma Vichara, the Self-quest? Can anyone judge for himself if he has the necessary competency?

Maharshi: This is an important preliminary question. Before Atma Vichara is started some antecedent experience, some achievement in the moral field is essential.

People having varied experiences in the world, at one stage develop a disgust or repulsion (vairagya) towards sense attractions or, at any rate, an indifference to such attractions, and feel forcibly the miserable transient nature of this body through which these attractions and enjoyments are had. This may be the result of the practice of devotion or some other upasana in this life, or of such devotion or other good works performed in previous lives.

People with minds thus purified and strengthened are the adhikaris, the ones competent to launch on Atma Vichara or enquiry into the Self; and these are the qualifications or signs by which one can determine such competency.

K.V.: As for these good works mentioned just now, such as snana, sandhya, japa, homa, swadhyaya, Deva puja, sankirtana, tirtha yatra, yagna, dana and vritas (i.e. ablution, sandhya vandana, or matin and vespers, repetition of mantras, fire-offering, study of holy script, worship of God, singing his praise or name, pilgrimages to holy places, the five Yagnas, charitable gifts, and holy vows), if these are needed merely to give a man competency for starting on Atma Vichara, and if a man has had sufficient viveka (discrimination between the Real and the unreal) and vairagya, dispassion, is there any use in such an adhikari carrying on the above, or are they merely a waste of his time and energy?

Maharshi: When an adhikari's raga (attachments) are fading away, these good works (sat karma) tend to chitta sudhita, further purify his mind. The positive good work done by body, mind or speech destroys the corresponding evil deeds (dush karma) he may have done through these – the body, mind or speech. But if the adhikari has no more stain left to work out in this way, his good works endure for the benefit of the world at large. The wise and perfect go on doing sat karma, good works.

What are the Granthis?

Chapter IX

14-8-1917

>Kavyakantha: What are the granthis and how are they cut off, as referred to in the famous line:

bhidyate hrdayagnanthish-chhidyante sarvasamshayaah

kshiiyante chaasya karmaani tasmin drshte paraavare 8.

When a person realises Him in both the high and the low,

the knots of the heart are loosened, his doubts dispelled and his karmas exhausted.

This has been the subject of doubt with several bhaktas. Will Maharshi please enlighten us on this matter?

Maharshi: Granthi is a knot. The knot of the heart ties two things together: the Supreme Brahman or Atma, and the appearance also of the jiva connected with a body. The location or contact between the body and Brahman is styled as the granthi or knot. It is by reason of that relation (or knot) that one gets the idea of a body, and the idea that he has or is a body. The body itself is inert, but Brahman is of the nature of Consciousness. The relation between these two is inferred by the intellect.

When the body is active in the waking and dreaming states, it is so by reason of its being overshadowed or covered by the image or reflection of the pure Chaitanya, i.e., Brahman. When, however, one is asleep, or for other reasons inactive and unconscious (e.g., in faint or coma), such image or reflection is absent, and from this fact the place of the Chaitanya or Brahman in the body is ascertained or located. It is located in the heart ( ![]() , hrdayam), into which the soul or ego retreats in deep sleep, ceasing its conscious activity in all parts of the body.

, hrdayam), into which the soul or ego retreats in deep sleep, ceasing its conscious activity in all parts of the body.

This heart is connected with a number of nadis (nerves) and the reflection of the Chaitanya on the heart spreads from the heart through these nadis or nerves into all parts of the body. The Chaitanya is subtle like electricity; and just as electricity, which in its manifest form is seen in lights, operates through solid material-like electric wires, so this Chaitanya Jyoti, or light of Brahman, moves from its subtle form through these nadis or nerves into the entire human frame. The sun, from its place in the heavens, illumines the entire solar system; so does Chaitanya Jyoti, or the light of Brahman, taking its place in the heart, illumine the entire human frame; and when such Chaitanya pervades every part of this body, then does the embodied soul, the jiva, derive all its experiences.

There are various powers manifest in the different nadis or nerves according to the function performed by each tissue or organ into which they (the nerves) enter. All such powers, however, are the various transformations of the one Chaitanya that permeates the nadis. But there is one nadi called the sushumna which is specifically the nadi prominently connected with the manifestation of the Chaitanya itself. It is also termed Atma-nadi or Amritanadi.

When man is operating through the other nadis alone, he derives the impression that the body is himself, and that the external world is different from him, and hence he is filled with abhimanam or dehabhimanam, i.e., 'I-am-the-body idea'.

When, however, he renounces these ideas (i.e., that the body is himself and that the world is different from himself) and expels the abhimanam (I-am-the-body idea) and enters on the enquiry into the Self, Atma Vichara, with concentration, then he is said to be "churning the nerves" (nadimathanam).

By such churning, the butter of the Atma or Self is separated from the nadis in all parts of the body and the Self shines in the Amrita or Atma-nadi.

Then is the Self or Brahman realised.

Then one perceives nothing but the Atman (Brahman) everywhere.

Such a person may have sense objects presented to him and yet, even when receiving those impressions, he will receive them as himself. Not as different from himself, which is the view of the ignorant.

In everything that he sees, the ignorant one perceives form.

The wise one perceives Brahman inside and outside of everything that he sees.

Such a person is said to be a Bhinna-granthi, i.e., the Knotless.

For him the knot which tied up matter or body with Brahman has been severed.

The term granthi or knot is applied both to the nadi-bandha, or physical knot in the nerves (something like the ganglia), and the abhimana or attachment to the body resulting therefrom.

The subtle jiva operates through these knots of nadis when he perceives gross-matter.

When the jiva retreats from all these nadis and rests in the one nadi, i.e. Atma-nadi, he is termed the Bhinna-granthi, or the Knotless; and his illumination results in his achieving Self-realization.

Let us take the case of a red-hot piece of iron. Here, what was formerly the cold, black iron is now seen suffused with and in the form of fire. Similarly, the one dull, cold and dark jiva, or even his body, when overpowered by the fire of Atma Vichara (knowledge of the Self), is perceived to be in the form of the Atman.

When a man reaches that stage, all the vasanas (tendencies), derived (it may be) from many previous lives and connected with the body, disappear.

The Atma, realising that it is not the body, realises also the idea that it is not the agent performing karma or action and that, consequently, the vasanas or fruits resulting from such (antecedent) karma do not attach to it (the Atman).

.As there is no other substance besides the Atman, no doubts can trouble that Atman.

The Atman that has once burst its knots asunder can never again be bound. That state is termed by some Parama Sakti (highest sakti) and by others Parama Santi (supreme peace).

Chapter XII

Kapali Sastri's questions:

K: Both the ignorant man and the man of Realization in their actual daily life perceive the experiencer, experience, and the objects experienced. How is the Realised one better off than the ignorant person?

Maharshi:

Because the Self-realised sees the unity of the Real amidst the multiplicity of appearances, whereas the ignorant man only sees and succumbs to the appearance of plurality.

The former sees himself, i.e., the experiencer, the objects experienced, and experience as one and the same Self, and the latter does not.

To the latter, who does not see the Self, everything is different.

K: In the Real (in which these differences appear) is there energy (Sakti)?

Maharshi: Yes! The Real includes all energy (Sakti).

K: But is that energy, within the Real, active?

Maharshi: Yes. It is active in producing these worlds. The active energy needs and has a support (asraya). That support is inactive and changeless though energy is active and changing. This activity and change is termed the "indescribable illusion" (maya). Illusion is manifold.

The apparent change, motion, or activity in the universe is itself an illusion.

The Real cannot and does not change.

The distinction between the Self and energy is an illusion.

If the sense-bound person changes his angle of vision, that distinction disappears, and the One alone remains.

K: Is the energy (of the Real, the Supreme) that produces all these worlds changing and transitory or changeless and eternal?

Maharshi: The Supreme that changes by reason of His energy is yet changeless. This profound mystery, sages alone can unravel.

Change is activity (vyapara) and activity is termed energy (Sakti). The Supreme created these worlds by His energy (Sakti). Activity being twofold — evolving (pravritti) and withdrawing (nivritti) — the Supreme also withdraws these worlds by His energy (Sakti), as the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, IV.5.15 states:

yatra tvasya sarvam-aatmaivaabhuut tatkena kam pashyetWhere, for one, everything has become Atma alone, what is there to be seen, and by whom?

In this passage relating to the activity of the Supreme in withdrawing (nivritti) the universe, first the term "everything" (sarva) is used. That refers to the multiplicity of appearances which prevailed at the time when duality was experienced. The other term "became" (abhut) refers to some activity. The term "Atma alone" (Atmaiva) expresses the fact that all differentiating activity is finally withdrawn into the Supreme Self (Atma) only. Thus we have the high authority of the Vedas to show that one Atma alone exists forever and is Real and that all else is illusory and evanescent.

K: Can we know the Real (Swarupa) without its activity?

Maharshi: No, we do not know the unmanifest Real apart from its manifesting activity.

Energy (Sakti), according to Saktas, has two names, the activity (vyapara) and support (asraya). Activity is creation, maintenance, re-absorption (pralaya), etc. The support is nothing but the Real, the Supreme (Swarupa). The Real is all, underlies all and needs the support of none. Such is the truth about the Real, its energy and activity. Multiform existence is the result of activity, and activity presupposes energy with the Supreme. When the Supreme is unclothed with energy, no activity arises, nor the Universe. In the endless whirl of creation and re-absorption, when re-absorption occurs, activity merges in the Supreme.

All human experience is impossible in the absence of energy (Sakti); no creation, no knowledge, and no triad can exist then. In the language of Saktas, Sakti (energy) is the Supreme, the one Real, and takes the name of activity (vyapara) in the act of creation, etc., and the name of Self (Swarupa) by reason of its being the support or sine-qua-non of activity.

If one considers that change (chalana) is the distinguishing characteristic of energy, then it must be admitted that we posit the existence of the Supreme Substance as that on which the play of energy or change takes place. That Supreme Substance is differently styled by different sets of persons. Some call it Sakti and others Swarupa; some call it Brahman, and others Purusha.

Reality (Satya) is to be viewed in two ways: first by its description and next by its nature or constitution, i.e., as the thing in itself. By description and name, that is, through speech, one tries to approach it and get an idea of it. But the Reality, as it is in itself, can only be realised; it cannot be expressed. The description given of it in the Vedas is:

yato vaa imaani bhuutaani jaayante

yena jaataani jiivanti

yat-prayantyabhisam-vishanti

tad-vijijnaasasva tad brahmetiTo him, verily, he said: Whence indeed these beings are born; whereby, when born, they live;

wherein, when departing, they enter; That seek thou to know; That is Brahman.

That Source, the maintenance, and end of all refers to its external attribute — activity, in order to give the learner an idea of it.

But the thing as it is in itself must only be immediately (directly) realised ( , aparokshaanubhuuti).

, aparokshaanubhuuti).

The wise (i.e., Vedantins) say that the basis or sine-qua-non of energy (Sakti) is the Self (Swarupa), and that its activity is its attribute.

By inquiring into the cause or root of that activity, one reaches its basis, the Self.

Substance and attribute, that is, Self and its basis are inseparable.

Let any one try to separate them, his mind retires baffled from the task. It is always by its attribute of activity that the Self is made known and (from this point of view) the attribute, activity, is therefore associated always with the Substance, the Self. But this activity is (in reality, from the point of view of the Self-realised) not distinct from the Eternal Self. The distinction between substance and attribute is the result of illusion. If the illusion disappears, the Self alone remains.

Chapter XIII

Women and Self-Realization

On the 21st of August, 1917, Kavyakantha Ganapati Sastri approached Maharshi to solve the following two doubts arising in the mind of Visalakshi, his wife, who had gone through Tara Vidya and Panchadasakshari Mantra Japa and other spiritual courses.

Question 1: If a woman has attained Self-realization and finds further stay as a member of a domestic circle a hindrance, can she, consistent with the Sastras, leave home and all and become a sanyasini or hamsini?

Maharshi: For those who are fully ripe in Self-realization there is no gender bar as to the assumption of sannyasa asrama in the Sastras.

Question 2: When such a lady is a Jivanmukta, i.e., released from bondage while in the flesh, and in that condition throws off her mortal coil, how should her body be dealt with, by cremation or by burial?

Maharshi: There is no difference between the sexes with respect to the attainment of Jnana, Realization, or Mukti, release from bondage. A female Jivanmukta's body should not be cremated, for a Jnani's body is a tabernacle of the Divine. Whatever objections are urged against the cremation of a male Jnani, apply with equal force to the cremation of a female Jnani's body.

Chapter XIV

Jivanmukti

On the night of the same day (21-8-1917), Venkatesa Sastriar came to Skandasramam and requested Maharshi to explain fully the state of Jivanmukti (i.e., release from bondage while yet in the flesh).

Maharshi:: A Jivanmukta is a person who, while yet in the flesh, has realised the Atman, and continues firmly in that state of Realization unaffected by the vasanas arising either from books or contact with the world.

Realization is only one. There is no difference in it; and freedom from bondage is also one and the same, alike for one who casts off the body and for the one who retains the body. It is the latter, however, who is referred to by the term Jivanmukta. The Scriptures say that such released or blessed souls are found in Satyaloka.

But in the matter of Realization, i.e. inner experience, there is no difference between the inhabitants of the Satyaloka and the Jivanmukta; nor is the experience of the Self-realised one who has cast off his body and become one with Brahman different from that of the above two.

All these three are equally free from bondage and equal in their realization of the Self. Salvation (Mukti) is the same, though to one with fixed ideas of difference, the experience may appear to be different in the above three cases.

The Scriptures say that the Jivanmukta's jiva (ego) is absorbed into Brahman even on this earth. When the Jivanmukta continues his tapas and it becomes mature, after some time he thereby develops several siddhis. Some develop the power to overcome the density in their body which thereafter ceases to be a matter for touch. Their bodies cease to be of dense material and become aerial, or like a flame of light, and are known as Pranavakara (i.e., of the form of Pranava, Om).

Yet others lose even that degree of substantiality and overcome even the rupa (form), rasa (taste), gandha (smell), etc. nature of the original human frame and become pure Chinmaya, thought-bodies. These siddhis may be attained very quickly in respect of their bodies by favour of the gods. There is no superiority or inferiority amongst the Self-realised to be inferred from the possession or non-possession of such siddhis. The Self-realised one is always free (Mukta).

Such freedom or Mukti is attained by the wise one who passes from his Sushumna-nadi in the upward path by the Archinathi Margam; by the light of wisdom emanating there, Mukti is attained.

By the Grace of the Lord, the upasaka whose mind is matured by yoga, attains this excellent Nadi-dwara Gati.

To him comes the power of traversing all worlds at pleasure, entering into any body at pleasure, and granting all boons to anyone at pleasure.

Some say that Kailasam (the Seat of Siva) is the place to which released souls go; others say it is Vaikuntam (the abode of Vishnu), yet others say it is Surya-Mandalam, the orb of the Sun. All these worlds to which these released souls go are as real and substantial as this world is. They are all created within the Swarupa by the wonderful power of Sakti.

Chapter XV

What are Sravana, Manana and Nididhyasana?

22-8-1912

Kavyakantha: Pray Sir, what are Sravana, Manana and Nididhyasana ?

Maharshi: These terms have several meanings – each to some extent derived from or connected with the other.

Take Sravana first: According to some, it is only the hearing of Scriptural texts (Veda vakya) with adequate explanation (Vyakhyana) from a Guru, which constitutes Sravana. But others disregard this and say even if what is taught is not the text from the Vedas or a comment thereon, but is couched in the vernacular, it is still Sravanam if (1) the Guru that imparts instruction is himself Self-realised, and (2) if his words throw light, i.e., teach Self-realization.

You may take it that (a) whether listening to the Guru's recital of scriptural texts or to the Guru's own words, or otherwise, by merit acquired in previous births, (b) or if the voice is heard within and an idea is formed in your mind that the underlying truth or root of the 'I-idea', or idea of personality, is not the body, then truly you have had Sravanam. Above all, note the fact that Sravanam is not the mere falling of sound on the ears.

It involves paying attention to Atma Vichara, enquiry into the Self.

Then let us take Manana:

Some say Manana is Sastrartha Vichara, or enquiry into the import or effect of Sastras (scripture). Well, it is more correct to note what is essential and say that Manana is devoting the mind to Atma Vichara, i.e., enquiry into the Self.

Finally let us consider what is Nididhyasana:

Some say that a thorough knowledge of Brahman or Atman is Nididhyasana, provided only that that knowledge be free from doubt and not conflict with the Sastras.

This definition, however, will fit in even for a bare intellectual grasp of the subject mentioned, even though it may be unattended by Realization. Mere study of the unity of jiva and Iswara from the Sastras does not ensure Realization, even if it be free from doubt or delusions such as 'I am the body and these phenomena are real, etc.' The mere study of hundreds of Sastras will not remove doubt and delusion.

No doubt these Sastras, studied with faith, do remove such doubt and delusion, but such removal is not permanent, as faith often weakens and the man begins to waver.

It is only Realization that can ensure a rooting out, i.e., the permanent removal of these obstacles of doubt and delusion.

When the mind or jiva goes through various outside experiences, even by exploring hundreds of Sastras, without realising and staying in the Atman, one does not obtain what is styled Aparoksha Jnana, i.e., Self-Illumination directly realised.

If, however, one has obtained such Realization, then one gets Sakshatkara, or immediate knowledge of the Self, and that is Moksha — that is the highest Nishta.

CHAPTER XVI

Bhakti (Devotion)

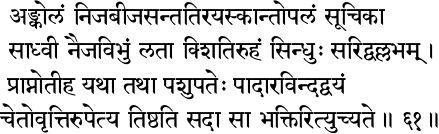

As the Ankola seed is attracted to its stem, the iron to the magnet, the wife to her lord, the creeper to its tree, the river to the ocean, so the soul attracted stands ever at the feet of the Lord. This attraction is termed devotion, Bhakti.

Kavyakantha: Will Maharshi please enlighten us on the subject of Devotion (Bhakti)?

Maharshi: To everyone the dearest object is himself. He loves himself always, and with the greatest love possible. Such an unbroken current of love, frequently compared in sacred books to a flowing stream of oil, is styled devotion, if it is directed towards God.

“Bhakti is the unshakeable attachment to the Supreme God.”

Ordinarily people regard God as existing outside of themselves and as having a personality like their own. The Jnani (enlightened sage) however regards the personal God (also) as none other than himself; and Self-love, in this case, is or becomes the love of God (personal). In his case, devotion is defined as Self-realization. Others, who treat the personal God as something outside themselves develop deep devotion to such a God and finally sink their personality in Him. The love-smitten chord of Self, trembles and passes in music out of sight. In fact, worship, nay, all intense concentrated thought or feeling, is the merging of the mind in the object worshipped or concentrated on. Intense faith in the personal God, however, carries the devotee easily and naturally to faith in and devotion to the impersonal Absolute (Swarupa Brahman). Mostly, the beginnings of devotion to (personal) God are traceable to a desire to avoid sorrows and attain happiness. So, with great keenness and zest people approach their God, investing Him with name and form, and attain the objects they desire. Even after such attainment, the habit of devotion continues and the mind trained to worship God with form and name develops the power to dwell on the Formless and Nameless. The evanescent objects achieved by the first flow of devotion to a personal God do not fully satisfy the aspiring soul who thirsts after enduring happiness. With this ever new impetus to seek something more than relative happiness, the progressing soul ultimately drops name and form as its object of contemplation and thus attempts to conceive of or realise the Absolute (Brahman). Thus devotion to a personal God gets transformed or ripened gradually into devotion to the Impersonal, which is the same as Vichara (enquiry) and Realization.

Investigation into the Self is nothing other than devotion.

Devotion may at the outset be by fits and starts. That need not depress the aspirant, for it will develop and become steadier and flow finally in an unbroken current. When devotion (personal) is ripe, a moment's instruction (Sravana) suffices for the next step in Jnana. Faith helps in the development of one's intuition and the attainment of complete illumination – Cosmic Consciousness. Thus, the weak aspirant's first efforts at devotion, through name and form at broken intervals, and for attaining finite or lower ends, ultimately carry him beyond all name and form, into an unbroken current of love to the Absolute. This is Salvation (Mukti).

No comments:

Post a Comment